History of Catholicism in Orkney

The first evidence of Christianity in Orkney can be dated to around 580 AD with the arrival of Cormac Ua Liatháin, a 6th-century Irish saint – this is recorded in Adomnan of Iona’s Vita Columbae. Cormac is portrayed as a dedicated anchorite, seeking isolated islands to lead a life of prayer and solitude, and is recognised for founding monasteries. More details can be found on the page for Orkney’s Lesser Known Saints. Additionally, an ogham-inscribed spindle whorl was found in Buckquoy, Birsay, with Christian sentiment in Old Irish language from around this time.

The Papar Monks

The early Christian monks known as the Papar, derived from the Latin “Papa” through Old Irish “Papar” meaning “Fathers,” were pivotal in spreading Christianity in Orkney. These monks pursued a monastic life of solitude in remote locations, often described as “deserts in the pathless sea.” They established monastic settlements on islands that came to be collectively known as the “Papey” islands.

In Orkney, there were originally three such islands, Papey Meiri, now called Papa Westray (or colloquially Papay), and Papey Minni, now called Papa Stronsay, and Pappawestre (now called Westray). These islands, along with many other locations in Orkney and Shetland, retain names that reference the Papar monks, highlighting the monks’ significant influence on the region’s place names and cultural history.

The enduring legacy of the Papar monks is evident through the Viking invasions starting in the 8th century, as these islands maintained their names despite the Norse incursions. The monks’ presence was substantial enough that the Norse settlers acknowledged and retained the names associated with the Papar, indicating a period of coexistence and possible mutual respect or tolerance. At this point, the Vikings were not Christian.

The history of the Papar in Orkney is further supported by the 12th-century Historia Norwegiæ, which mentions the Papar as being present when the Norse arrived. This document suggests that the Papar monks were already established in the region and that their settlements often predated Norse colonisation. Archaeological evidence from these sites corroborates early Christian activity, providing tangible proof of the Papar’s early and enduring presence.

The Papar Project has played a crucial role in documenting and analysing the distribution and significance of these place names. Research has shown that Papar settlements were frequently located on fertile land, which was likely attractive to both the monks and later Norse settlers. Placenames associated with the Papar also include Paplay (placenames in South Ronaldsay, Holm and Eday) as well as Papdale in Kirkwall.

Arrival of the Vikings

Until this point, Orkney had been inhabited by native folk, Picts and Irish monks. It was then colonised and later annexed by the Kingdom of Norway in 875 and settled by the Norsemen. Christianity was first introduced to Norway by King Håkon the Good (c. 920–961) and was carried on by Olaf Tryggvason who founded the city of Niðaros and laboured to spread Christianity in Norway, Orkney, Shetland, Faroe, Iceland and Greenland.

Orkney then came under the authority of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nidaros, under the See of Niðaros Cathedral, in Trondheim, Norway.

The Brough of Deerness, located on a cliff promontory on the rugged coast south of Mull Head, is home to the ruins of a Norse chapel thought to date back to the 10th century. Excavations in the mid-1970s revealed postholes and grooves indicating the lines of an earlier timber chapel with a wooden altar, suggesting a pre-Norse, possibly Pictish origin. This evidence implies that Christianity was practised in Orkney before 995. The chapel, possibly founded by Thorkel near his Hall, paralleled other monastic sites like Bamburgh and Lindisfarne. The remains include graves of two infants buried in the Christian manner, though no burial ground for elderly monks has been found, supporting theories that it may have been a secular, defended settlement during the early Norse period. An Anglo-Saxon coin from the reign of Eadgar (959-975) was also discovered, further attesting to the site’s historical significance. This suggests it was one of the first Viking chapels in Orkney.

The chapel was re-founded in the 11th or 12th century following the Norse conversion to Christianity, and it was rebuilt in stone with a low perimeter wall. The stone structure visible today, characterized by walls that originally stood about four feet high, eventually fell into disuse and was later damaged by naval target practice during World War I. The site also includes numerous turf-covered rectangular buildings and enigmatic circular depressions, previously mistaken for Celtic beehive huts but likely shell holes. Despite the challenging conditions, the site continued in use until the 16th century, when it saw some improvements like the installation of a flagstone floor before being abandoned. Today, the Brough of Deerness remains an evocative reminder of the island’s early Christian heritage and Norse history.

Pope Eugene III established the bishopric of Orkney in 1070. At this time, the bishopric appears to have been suffragan of the Archbishop of York (with intermittent control exercised by the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen) until the creation of the Archbishopric of Trondheim (Niðaros) in 1152.

On the Brough of Birsay, the first settlement on this site was a possibly 6th-century Celtic monastic establishment, the chapel, grave-yard (beneath that of the later Norse settlement), and enclosing wall, according to Canmore. The name of St Columba or St Colm has been associated with the site, so possibly the mission of Saint Cormac, but not on very good authority. Around 1100 a Romanesque style church was built on the island atop the previous settlement. It consists of a rectangular nave, chancel and apse, with a stone bench around the walls of the nave. The church is set within a rectangular churchyard, and immediately to the north of the church, several buildings are grouped around what appears to be a cloister. The surrounding buildings include a blacksmith and a sauna. Although there is no documentary evidence to support it, this appears to be a small monastic establishment, probably either Benedictine or Augustine.

While this was happening, perhaps the most important events in Orkney’s history were unfolding. Saint Magnus was martyred in 1117. The construction of St. Magnus Cathedral began in 1137, and Earl Rognvald Kali Kolsson died in 1158. The full story of these events is told on our page for Saint Magnus and Saint Rögnvald.

In 1153-1154 the bishopric of Orkney came firmly into the Scandinavian fold, as opposed to the York or St Andrew’s fold, when Pope Adrian IV arrived in Norway to formally establish the new Archbishopric of Trondheim (Niðaros), embracing the Orcadian See.

The period between c.1050 to c.1250 saw an explosion in ecclesiastical sites in Orkney.

The first bishop of Orkney was William the Old, bishop from 1102-1168. It was for Bishop William that the nearby Bishop’s Palace was built. The Bishop of Orkney from 1188 until his death on 15 September 1223 was Orkney born Bishop Bjarni. It was he who exhumed the relics of Saint Rögnvald and added an extension to the cathedral.

In 1263 King Håkon Håkonsson (Håkon IV) withdrew to Orkney to stay for the winter during the Battle of Largs. Around this time a delegation of Irish kings invited Haakon to become the High King of Ireland and expel the Anglo-Norman settlers in Ireland, but this was apparently rejected against Håkon’s wish. Håkon had planned to resume his campaign the next year, however, during his stay in Kirkwall he fell ill and died in the early hours of 16 December 1263. He was buried in the St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall for the winter; in spring, his body was exhumed and taken back to Norway, where he was buried in the Old Cathedral in his capital Bergen.

In 1296 and before Orkney belonged to Scotland, Edward I of England invaded Scotland, marking the start of the Wars of Scottish Independence. This reached its peak in 1314 with the Battle of Bannockburn in which Robert the Bruce achieved a decisive victory over the English resulting in the 1328 Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton which recognised Scotland’s independence.

In 1472 Orkney left the Kalmar Union – Christian I pledged the Northern Isles to James III of Scotland as insurance for his daughter’s, Margaret of Denmark, dowery in 1468; the dowery was not paid, and the islands transferred to perpetual Scottish sovereignty in 1470. The Parliament of Scotland absorbed the Earldom of Orkney into the Kingdom of Scotland.

The Orkney See remained under the nominal control of Trondheim until the creation of the Archbishopric of St Andrew’s in 1472 when it became for the first time an officially Scottish bishopric.

On 9 April 1526 Bishop Robert Maxwell was appointed Bishop of Orkney. It was he who installed the cathedral bells. These were complemented by a rich church life at the time, with over 30 priests, Gregorian chant, organ music, vivid frescoes (see photo below) that decorated the walls and ceilings and beautiful vestments and candles. The community was also involved with Corpus Christi processions through Kirkwall, and had many paid holidays throughout the year. Furthermore, as a regular meeting place of important people, the kirk green was established, providing a place to practice archery.

Henry VIII founded the Anglican Church in 1534, which eventually led to the Scottish Episcopal Church in Scotland, including Orkney. Shortly after, Robert Reid was appointed Catholic Bishop of Orkney. He set about renewal and building works, including setting up a grammar school in Orkney to teach the ‘boys of the choir’ and ‘the poor people who are willing to be taught’ beside the cathedral. We know also at this time St. Magnus Cathedral had an organ and a library. It was the role of bishop at that time to oversee revenue, worship, education, hospitals, almshouses, clergy and other orders in addition to various other political duties.

Economic and cultural links to now-Lutheran Scandinavia aroused little enthusiasm for change among Orkney’s merchants in the mid-sixteenth century. The Scottish Reformation in 1560 saw the Scottish Parliament officially adopt the Reformed faith and the Church of Scotland was founded. They abolished all Catholic ecclesiastical structures and rendered Catholic practice illegal in Scotland. During the Reformation, many cathedrals suffered significant damage, but St. Magnus Cathedral appears to have escaped relatively unharmed. However, its organ, treasures, and rich vestments were removed, and the beautiful frescos were concealed with whitewash and the shrine of Magnus was dismantled. The bones of the saint disappeared, presumed destroyed. Early the following year, the Presbyterian Bishop Bothwell came to a meeting in Kirkwall of the traditional Norse folk and urged the islanders to “be content of mutation of religion”. It caused a commotion, and the bishop had to hide in his palace while riots raged outside and the locals brought in chaplains to say Mass and celebrate sacraments. Over time, change was imposed however, and accepted as ministers were installed from mainland Scotland.

Immediate Aftermath of the Reformation (1560-1600)

The Scottish Parliament passed laws in 1560 that outlawed the celebration of the Catholic Mass and required all citizens to adhere to the Protestant faith. Catholic practices were banned, and adherence to Catholicism was punishable by law. Catholics were subject to fines, imprisonment, and confiscation of property if they were found practising their faith. Clergy who refused to convert to Protestantism were particularly targeted. Catholics faced social ostracism and were excluded from public office and positions of influence. They were often viewed with suspicion and hostility by their Protestant neighbours.

In most of Scotland, Catholicism became an underground faith in private households, connected by ties of kinship. This reliance on the household meant that women often became important as the upholders and transmitters of the faith, such as in the case of Lady Fernihurst in the Borders. They transformed their households into centres of religious activity and offered places of safety for priests. Meanwhile, in Orkney as elsewhere, crucifixes and statues were burned, holidays were banned and it was forbidden to dress the kitchen table any more decoratively on holy days than normal days. It was dangerous to attempt to say Mass or practice Catholic faith as all elders of the church kept a close eye in the community.

At this time, underground Catholic worship and tradition is evidenced to have continued. Records from 1584 in South Ronaldsay show various Holy Days being observed and women attending ruined churches to give thanks for childbirth. Catholic burials continued on the isles, the cult of St Tredwell continued on Papay and Stromness folk celebrated the feast day of their local churches, and Saint Peter the Patron Saint of Stromness. Officially though, the Papish had been eradicated.

While Irish Franciscans evangelised in the Western Isles and Outer Hebrides, no strong missionary effort was noted in Orkney. A Lazarist working in the northern Highlands wrote in 1657 to St Vincent de Paul about his activities: “I even went to the Orkney Islands.” Additionally, Jesuit priests and other missionaries from Ireland visited Orkney in disguise as merchant sailors. In secret they baptised, gave Holy Communion and the sacrament of penance. But all this was to no significant effect as countering the forces of the state proved impossible.

Despite the lack of Catholics, Presbyterian ministers reported worry about the behaviour of many Orcadians. They observed a range of old-fashioned, “superstitious” customs and rituals: charms involving snippets of Latin prayer; reluctance to work on feast days of saints to whom kirks were dedicated; the lighting of midsummer “Johnsmas” bonfires. (Indeed, the lighting of the Beltane Fires also makes its way into the modern Orkney Anthem – “Tae the gleams that break in the midnight wake, Tae the blaze o’ the Beltane fires” – a nod to the Irish Catholic missionaries who settled Orkney and brought with them their traditions). The Orkney protestant ministers complained about habits of pilgrimage to ruined chapels, undertaken to restore health, such as the healing loch of Saint Tredwell in Papa Westray, or to the Brough of Deerness. It is noteworthy also that coins from the 17th-20th centuries have been found in Loch Tredwell and other coins found at the Brough of Deerness and the ruins of other small parish churches. Pilgrims were also known to frequent the many Holy Wells around Orkney, the most well-known these days being the Haley Hole, known today as Hellihole Road in Stromness.

There were further Holy Wells with famous traditions regarding sacred water in Orkney; At Bunton in Stronsay there are three holy wells which are collectively called the Well of Kildinguie (Marwick 1927: 71). According to Barry, this well is a set of three mineral springs that differs in strength (Barry 1867 : 52). Tradition says that it was held in such high repute that people came from Denmark and Norway to drink its water, and on the sandy shore about two miles south-east of the Well of Kildinguie there was a place called Guiyidn where people could collect and consume a seaweed called dulse. The water from the holy well, the dulse and the fresh air in Stronsay would ‘cure all maladies except the black death‘ (Anderson 1794 325). In the parish of Sandwick there were two holy wells, one superior to the other: One was called Crossikeld in a spot called Forsewell that possessed curative powers superior to the well in Kirkness township. There was a well in Kirkness(sic) was dedicated to St Margaret and was believed to possess healing powers (Fraser 1924 : 27). In the parish of Stenness there is a local tradition of a holy well at

Bigswell below the Ring of Brodgar, and it was thought that the water was to some extent curative (Fraser 1926: 23).

17th Century: Continued Discrimination

When James VI of Scotland became James I of England and Ireland in 1603, he pursued a somewhat more lenient policy towards Catholics, especially in England. However, in Scotland, strict anti-Catholic laws remained largely in place, though enforcement varied.

In 1614, Government forces besieged and destroyed Kirkwall Castle whilst suppressing a political rebellion. They also intended to destroy St. Magnus Cathedral when the rebels took refuge there. Thankfully, Bishop James Law managed to prevent them from carrying out this plan.

Charles I’s attempts to introduce Anglican practices faced resistance in Scotland, which was predominantly Presbyterian. While he did not directly support Catholicism, his actions increased religious tensions and suspicion towards any form of religious deviation from Presbyterianism.

During the Cromwellian Era (1650-1660), Cromwell’s invasion and subsequent control of Scotland brought a temporary period of relative toleration, as Cromwell’s regime was more focused on political control and less on enforcing religious uniformity. Nevertheless, Catholics did not enjoy full religious freedom and were still marginalised. In 1652, Saint Magnus’ Cathedral, by this stage Church of Scotland, suffered damage from a garrison of Cromwell troops sent to Orkney and built their fort on what is today Cromwell Road, around Wayland Park.

His soldiers seized the Cathedral for their barracks and had iron rings hammered into the pillars, used to tether horses as they were stabled inside the Cathedral. Marble slabs covering the tomb of Bishop Tulloch which for years had been where Orcadians would pay their debts were taken apart.

The public in Orkney were generally royalists, and so the military occupation had little popular support, save for a minority of the Presbyterian clergy and 2 Kirkwall Burgh men.

The Glorious Revolution (1688) saw the overthrow of the Catholic King James VII of Scotland (James II of England) who had converted to Catholicism before he became king and sought to implement both Catholic Emancipation and freedom of religion. This resulted in the ascension of the Protestant William III, a Dutch Calvinist, and Mary II and with this came the reinforcement of anti-Catholic laws.

These Penal Laws imposed severe restrictions on Catholics, barring them from holding public office, serving in the military, and owning land. Catholic worship was driven underground, and priests were subject to arrest.

In Scotland, members of the Church worked in secret to train young men for the priesthood. As it was unsafe to advertise the fact that young men were being trained for the Roman Catholic priesthood in Protestant Scotland, secret colleges were set up in various out-of-the-way places in the Highlands and Islands. It is not known to what extent Catholicism managed to persist in Orkney during this period.

1707 saw the Acts of Union creating the Kingdom of Great Britain, merging Scotland and England. This century also saw the Jacobite uprising and the Battle of Culloden. It was in this same year the Church of Scotland minister Revd. John Brand wrote that of Orkney that several isles have saints days which are still observed. This includes on Rousay a day during the harvest that no work should be done, “lest the ridges bleed”. He stated that should “popery get footing… again many of the inhabitants of these isles would readily embrace it, and by retaining some of these old popish rites and customs, seem to be in a manner prepared for it.” In terms of other Catholic traditions, he continues that when farm animals are sick they get sprinkled with “fore-spoken-water”, as they do also to their boats. Especially on “Hallow-even, they used to sein or sign their boats and put a cross of tar upon them… their houses also some use then to sein“. Further Church of Scotland observations of Kirkwall continue:

“…many of the lower class of people are still so ignorant as to be under the baneful influence of superstition. In many days of the year they will neither go to sear in search of fish, nor perform any sort of work at home. In the time of sickness or danger, they often make vows to this or the other favourite saint, at whose church or chapel they lodge a piece of money, as a reward for their protection“.

By the late 18th century, attitudes began to soften. The Papists Act of 1778 and subsequent legislation started to alleviate some of the restrictions on Catholics, although full civil rights were not restored until the 19th century. In 1790, Bishop Geddes, after visiting both Kirkwall and Sanday, wrote that he was treated well by two Balfours who remained steadfast in the Catholic religion.

It seems that through this period, Saint Magnus Cathedral had fallen into significant neglect and disrepair. On 29 August 1834, Walter Lovi wrote to Bishop Kyle about Saint Magnus Cathedral:

“…But though used as a Kirk it is kept in wretched order. The pillars are covered with green mould; and there is a degree of damp that must soon bring the whole to decay.”

A Doctor Wood collected a list of charms and verses used by the folk on Sanday in 1836 for different types of sickness, from toothache to burns or bleeding. These are documented in Alison Gray’s book “Circle of Light – The Catholic Church in Orkney since 1560“.

In 1845, the Government assumed ownership of Saint Magnus Cathedral, displacing the Church of Scotland congregation at the time and undertaking extensive restoration work on the building. Ownership of the Cathedral was returned to the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall in 1851, leading to the installation of new pews and galleries in the choir and presbytery for the reinstated congregation.

Ownership of the Cathedral was returned to the Royal Burgh of Kirkwall in 1851, leading to the installation of new pews and galleries in the choir and presbytery for the reinstated congregation.

On 20 December 1860 a provisory Chapel of Kirkwall was opened in Bridge Street Lane (now St. Olaf’s Wynd). Mass was said by Rev. Father Stephan and assisted by a priest from Lerwick, and the sacrament of Confirmation was given. This was not well received by the local community as the chapel was subjected to broken windows, vandalism and people yelled abuse at parishioners throughout the 1860s. Additionally, the priest, chapel and Catholic Church more generally were the subject of many abusive articles and letters in The Orcadian newspaper, pointing to a fear and ridicule of “popery”. At the time, the community was served by Father Capron. Capron arranged for a schoolmaster to come to Orkney, Thomas Fitzpatrick, to teach the Catholic school-children.

On 4th March 1878, Pope Leo XIII re-established the Scottish hierarchy of bishops. This meant that Scotland was officially no longer classified as a missionary country but administered by its own system of bishops. After hundreds of years of persecution, Catholicism was once again allowed to flourish in Scotland.

Orkney Moved to the Arctic Missions

On 17th November 1860 (pdf), Pius IX approved the establishment of a prefecture apostolic of the Arctic Pole which included territories running from Hudson Bay in Canada to the Lapland regions of Scandinavia, with its headquarters in Wick, Caithness, but subsequently transferred on 10th April 1866 to Copenhagen, Denmark. To this prefecture were transferred from the Northern District the County of Caithness and the Orkney and Shetland Isles. By 1872 the prefecture had closed and the Scottish territories, including Orkney, reverted to the Northern District.

The County of Caithness, along with the Orkneys and Shetland, which lately formed a part of the Northern District, are now placed under the jurisdiction of the Prefect Apostolic of the Arctic Missions, whose care extends over Iceland, the Faroes, Greenland, Lapland, part of Hudson’s Bay, Orkney, Shetland, and Caithness-shire.

These Arctic Missions were established by our Holy Father Pope Pius IX., after the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, for the evangelisation of the poor people who live in the frozen regions towards the North Pole.

By a decree dated 10th April 1866, his Holiness has appointed Copenhagen, in Denmark, as the residence of the Prefect Apostolic of the Arctic Missions.

The Clergy already attached to these missions are:

- The Very Rev. B. Bernard, Prefect Apostolic, Copenhagen.

- Rev. P. J. Capron and Rev. H. Van Wtberghe, at Wick, Caithness-shire ; the latter attends the Orkneys.

- Rev. A. Boiler and Rev. F. Plasse, at Tromso; and

- Rev. E. Maesfrancx and Rev. Cl. Dumahut, at Altengaard, both stations in Lapland.

- Rev. G. Bauer and Rev. J. M. Convers, at Thorshavn, in the Faroes.

- Rev. J. B. Baudoin and Rev. E. M. Dekiere, at Reykjavik ; Rev. H. Blancke, at Akureyri, both stations in Iceland.

- Rev. Th. Verstraeten, at Lerwick, in the Shetland Isles.

There are also, in different colleges for these missions, ten students, two of whom - will, please God, be ordained priests this year.

At Wick there is a modest chapel and chapel-house. A school has now been built in this station, and it is earnestly hoped that the work may soon be finished, and the house modestly furnished and made ready for the good Sisters, the “ Faithful Companions of Jesus.” May Almighty God send down His most precious blessings upon all those kind hearts who have so generously contributed towards bringing this much-desired good work so near its happy termination.

At Lerwick also, in 1865, a house, with ground for the erection of a chapel, has been purchased and paid ; and for this thanks are due to the Faithful of (Scotland, who so readily responded to the appeal made for that purpose to their charity. It is hoped that they will not leave the good work half-way.

The charitable are also reminded that, besides this station at Lerwick, there is another in almost equal distress at Kirkwall, in the Orkneys, where there are already several Catholic families, and that the Arctic Mission - without question one of the poorest and most difficult on the face of the globe - has to go on and impart the blessings of religion to the unfortunate inhabitants of the Polar regions.

Much has been done already, but a great deal remains to be done yet. Besides other most urgent wants, which the necessity of further developing his extensive and desolate mission presses upon the Prefect Apostolic, he wishes as soon as possible to finish the good work at Wick, to build the Chapel at Lerwick, and to set in order the distressed station at Kirkwall. But to accomplish these important objects, and to promote the arduous task of spreading the Gospel in the forlorn frozen regions of the High North, the Mission is utterly powerless, unless the charitable Faithful lend it a helping hand. An appeal is therefore made to the Catholics of the United Kingdom in behalf of their remote countrymen, as well as of the yet more helpless tribes whose lot is cast among icy seas, frozen lands, and snow-clad mountains.

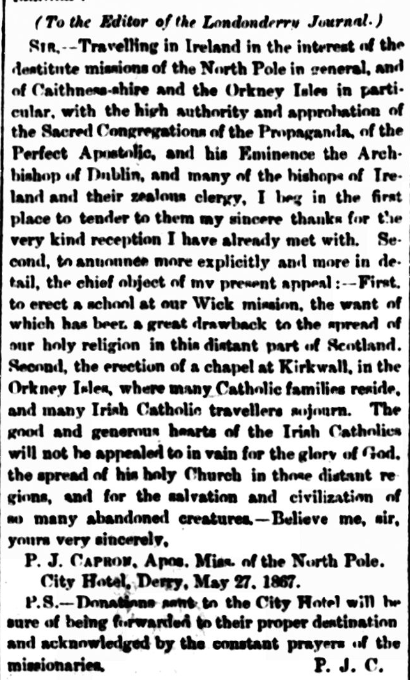

It was the Rev. P.J. Capron who took upon himself the mission of establishing a dedicated Roman Catholic Church in Kirkwall, the first since the Reformation, after receiving permission from Rev. John McDonald, Vicar Apostolic of the Northern District (and subsequently Bishop of the newly restored Catholic Diocese of Aberdeen). Capron’s presence both Wick and Kirkwall caused some controversy as attitudes of Protestants towards Catholics were inflamed at the time. Capron set about a major fundraising project, which included travelling to Ireland to appeal for funds from the faithful.

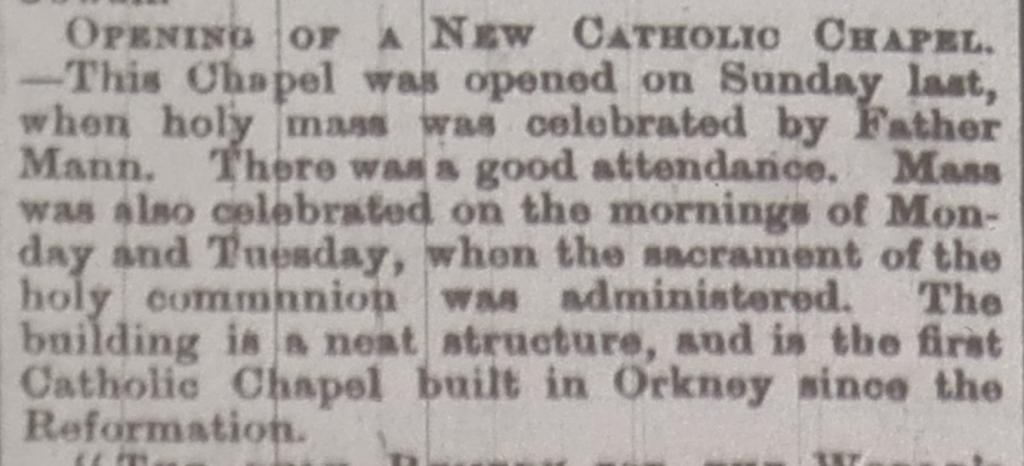

By 1877 his fundraising efforts had borne success and Our Lady & St. Joseph’s of Kirkwall was formally established with its first Mass on Sunday 23rd September 1877. By this stage, Orkney had a new priest, Rev. William Mann. The building was erected by the firm Wm Firth and Robert Fea on land known as “Groat’s Garden”. The land belonged to Robert Scarth of Binscarth.

Saint Magnus Cathedral in the 20th Century

In Kirkwall, the Cathedral fell into disrepair until the early 20th century, when The Thoms Bequest enabled significant restoration efforts. Between 1913 and 1930, the Cathedral underwent major exterior alterations, including the construction of a tall steeple to replace the low pyramidal roof of the bell tower. Internally, changes included the removal of the screen separating the choir from the nave, along with the removal of pews and galleries. Plain windows were replaced with stained glass, the floor was extensively tiled, and warm red sandstone was revealed by stripping away plaster and whitewash. It was during this period of construction in March 1919 that the relics of Saint Magnus and Saint Rögnvald were discovered inside the pillars of Saint Magnus Cathedral. The relics were returned to the same location to rest there in peace.

World War II and the Italian Chapel

The outbreak of World War II saw the British forces decide that Scapa Flow was a crucial anchorage for the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet due to its strategic position and natural defenses. The German navy took advantage of this to launch a torpedo attack on HMS Royal Oak, leading to the loss of 835 men and boys. In response, and in order to protect Scapa Flow from such attacks Winston Churchill ordered barriers to be constructed to the east of Scapa Flow between various islands. The labour for this would be supplied by setting to work Italian prisoners of war captured in north Africa. These prisoners had seemingly very good relationships with both the camp commanders and the local Orkney population. They set about converting two under-utilised Nissen huts into a beautiful Catholic chapel. You can read more about this on our dedicated page about the Italian Chapel.

During this time there was a colossal influx of British military into Orkney. Rev W. Davies was parish priest during World War 2 – however numerous chaplains to the forces preached at Lyness in Hoy, and perhaps likely provided relief at Kirkwall.

For some period of time during the 20th century there were Catholic chapels in Rousay (Charlie Wilkinson’s at Breck), Hoxa (Howe) and Stromness (Braemar).

Today the cathedral is owned by Orkney Islands Council in lieu of the people of Orkney. Therefore it is available to use by any Christian denomination as well as secular events. The Cathedral is still considered a consecrated ground in the Catholic Church and remains a Catholic consecrated place of worship.

St Magnus Cathedral Mass to Commemorate the 900th Anniversary of the Martyrdom of St.Magnus –Sunday, 30th July 2017

Between 2019 and 2021 survey work was undertaken to document and record the graffiti in the stonework of St Magnus Cathedral. Several markings of “VV” or “virgo virginum” (Virgin of Virgins) were found. There was also a hexafoil design on the Paplay family tomb, a motif designed to lure in evil spirits, only to capture them in a circle for eternity. There is a chevron carved into the 16th century Bishop’s door (perhaps a bishop’s mitre) and some inscriptions marking a location – perhaps the location of the burial of some bishops within the church, perhaps under the choir stalls. Throughout there are signs of pecking, speckled holes, which are thought to have been collected by devotees to take home, perhaps to mix into drinks to cure illness. Other markings include a Greek cross and at least 15 other religious inscriptions. Two consecration crosses were also found from the time the cathedral was originally consecrated.

Our Lady & St. Joseph’s was re-ordered in 1982 in keeping with changes introduced by Vatican II. While these changes were taking place, Mass was said in St Rognvald’s chapel in Saint Magnus Cathedral. Father Herbert Bamber had been parish priest in Orkney from 1963-1981. When he died in March 1992 aged 85, Rev. Ron Ferguson held a memorial service in St Magnus Cathedral for him. This was the first time Catholic mass had been held in St Magnus cathedral since the Reformation. The Right Revd. Bishop Mario Conti in 1995 was the first Catholic bishop to preach in St Magnus since the reformation. Additionally, requiem mass for George Mackay Brown, devoted to Catholicism and St Magnus, was held on St Magnus day 4th April 1996 by Fr Michael Spence SJ and Fr Jock Dalrymple.

In 1999, The Transalpine Redemptorists society of monks purchased the island of Papa Stronsay and established a monastic community there. Until June of 2008, the monks were considered renegades, frozen out by the Holy See. Known as the Transalpine Redemptorists, they broke away from Rome in 1988 in a dispute over their right to celebrate mass in Latin. In 2007, when Pope Benedict XVI reinstated the Latin mass, Father Michael Mary, the head of the monastery on Papa Stronsay, took tentative steps towards reconciliation. With two other Transalpine Redemptorist priests, he travelled to Rome to ask for permission to celebrate mass in Latin at their monastery and a chapel on Stronsay and to have their “censures” – an ecclesiastical penalty imposed on them when they broke away – lifted. They agreed to change their name to Sons of the Most Holy Redeemer and defect from the Society of St Pius X to the Priestly Fraternity of St Peter, a group of traditionalists in good standing with the Holy See. You can read more about the Sons of the Most Holy Redeemer on their website where they live-stream Mass in Latin.

In late 2006, Our Lady & St. Joseph’s Parish Church suffered extensive flooding. Most of the interior was very badly damaged and significant renovations were required. During this time we held our celebrations of Mass in Saint Magnus Cathedral.

In 2020, 3 hermits living on Westray were excommunicated for hate-speech comments on a blog they ran. Previously from Nottinghamshire, “The Black Hermits” of two men who called themselves a priest and a monk were among the group, along with a woman who was a doctor. A spokesman for the Diocese of Argyll & the Isles said: “In April the group wrote to Bishop McGee to say they intended to withdraw their ‘obedience from Pope Francis and sever communion with the Holy See.’ The bishop advised them that their actions would incur automatic excommunication and urged them to reconsider and made several offers of dialogue all of which were refused.

The Catholic community in Orkney, and in particular Our Lady and Saint Joseph’s, is a vibrant community today. While our numbers are not as high as in times gone by we are a kind and supportive community, and we welcome all visitors to celebrate Mass with us.